domingo, 29 de abril de 2012

Escenografias Clamorosas: TURANDOT, de Nuria Espert y Ezio Frigerio.

con la que se reabrió el teatro barcelonés en 1999, tras el incendio que lo arrasó en 1994.

"Turandot" -situada en la corte imperial de Pekín, con grandes masas corales y una brillante ritualización de la acción- quería ser, ya en la época en que se estrenó en Milán (1926), un gran espectáculo. Por eso la dramaturgia que ideó Núria Espert cumple ampliamente este objetivo.

El espacio escénico grandioso, diseñado por Espert, sirve para expresar el poder absoluto del emperador chino y, por tanto, de Turandot, que decide con una arbitrariedad cruel la vida o la muerte de sus pretendientes, que quiere vivir sin compartir la vida con nadie, y que es, como dice el texto, "blanca como el jade y fría como la espada".

La visión que da esta producción del poder quiere subrayar justamente que se trata de un poder que se afirma muy por encima de la multitud anónima y que paraliza de terror a todos los que se acercan.

Por eso también la multitud anónima está caracterizada como una masa impersonal, tal como parece subrayar la luz monocroma -azul noche o gris- que la define en esta producción.

Una de las singularidades de este "Turandot", exclusiva de la producción del Gran Teatro del Liceo, es el desenlace.

Puccini no acabó la ópera porque la muerte lo sorprendió en Bruselas (1924) sin tener resuelto el final. En la dramaturgia de Núria Espert se opta por combinar las dos versiones del desenlace que hizo Alfani y, finalmente, Turandot, tras reconocer que el amor domina ya sus sentimientos y consciente de que esto le debilita y le derrota, prefiere suicidarse antes de entregarse al extranjero.

jueves, 26 de abril de 2012

Escenografias Clamorosas: El Anillo de Lepage (II)

Iain Paterson as Gunther, Wendy Bryn Harmer as Gutrune, Deborah Voigt as Brünnhilde and company of 'Götterdämmerung' (Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera)

Stephanie Blythe as Fricka and Bryn Terfel as Wotan in Wagner's Die Walküre (Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera)

Jay Hunter Morris as Siegfried, Wendy Bryn Harmer as Gutrune, Iain Paterson as Gunther and Hans-Peter König as Hagen

Waltraud Meier as Waltraute

Escenografias Clamorosas: Der Ring (Lepage)

"El anillo de los Nibelungos" de Wagner viaja al futuro en el Met de Nueva York en una escenografia innovadora que a mi particularmente me encanta!

Retrofuturista, minimalista y potente, la nueva producción de "El

Anillo de los Nibelungos" de Wagner presentada en forma completa este

mes en la Metropolitan Opera de Nueva York da una nueva vuelta de tuerca

a la obra operística más famosa de la historia.

La nueva

versión de la tetralogía ("El oro del Rhin", "La Valquiria", "Sigfrido" y

"El ocaso de los Dioses") ideada por el director teatral canadiense

Robert Lepage es considerada la "producción más ambiciosa" de la Met y

la primera en más de 20 años, con un costo de 16 millones de dólares.

Si bien las cuatro óperas ya habían sido estrenadas en forma

individual, el martes por la noche concluyó la primera de los tres

sesiones a través de las cuales los espectadores pueden ver la

tetralogía de Richard Wagner (1813-1883) en orden cronológico en un

espacio de tres a dos semanas.

El gran protagonista de la serie

de óperas de una duración total de 16 horas es "La máquina", una

gigantesca estructura móvil de 24 planchas de aluminio concebida por

Lepage como parte fundamental del escenario y que se asemeja en cierto

modo al teclado de un piano.

Esta innovadora y a veces ruidosa

maquinaria, de 45 toneladas, da un marco futurista y minimalista a la

acción, permite proyecciones y recrea ríos, bosques y montañas.

Con este marco, los personajes parecen surgidos de películas de culto

donde el futuro se roza con lo épico como "Blade Runner" o "La Guerra de

las Galaxias".

El elenco es amplio, aunque destacan el

barítono galés Bryn Terfel en el papel de "Wotan", la soprano

estadounidense Deborah Voigt como "Brünnhilde" y el tenor también

estadounidense Jay Hunter Morris como "Sigfrido". El italiano Fabio Lisi

es el director de orquesta.

La puesta en escena crea por

momentos escenas de una extraordinaria belleza visual, como en el baile

de las ninfas al inicio de "El oro del Rhin", donde las cantantes

literalmente flotan delante de la burbujeante agua del río proyectada

sobre las teclas en forma vertical.

Otro momento sublime es sin

lugar a dudas la mítica "Cabalgata de las Valquirias" del tercer acto

de "La Valquiria", con las planchas metálicas sirviendo de caballos de

las semidiosas encargadas de recoger a los héroes caídos en batalla para

llevarlos al Valhalla.

Sin embargo, la arriesgada estructura

ideada por Lepage también tiene sus limitaciones y en algunas partes,

por ejemplo en "Sigfrido", se vuelve algo recurrente.

Algunos

medios, como The New Yorker, han sido muy críticos con la apuesta de

Lepage: "Libra por libra, tonelada por tonelada, es la más estúpida y

derrochadora producción de la historia moderna de la ópera", dijo la

prestigiosa revista.

Para el director teatral canadiense,

repensar la tetralogía y llevarla al escenario es una de esas ocasiones

que se presentan una vez en la vida y su intención es "tratar de ver

cómo podemos contar en nuestra época esta historia clásica de la manera

más completa".

"Trato de ser extremadamente respetuoso con la

historia de Wagner, pero en un contexto muy moderno (...). El 'Anillo'

es una de esas raras oportunidades en la que uno trabaja en una empresa

tan inmensa. No es sólo una historia, no es sólo una ópera o una serie

de óperas: es un cosmos", afirma en el sitio de la Met.

Richard

Wagner pasó 26 años escribiendo la tetralogía, que combina el poema

épico "El Cantar de los Nibelungos" con otros mitos y leyendas

germánicos para dar vida a una trama que gira en torno a la posesión de

un anillo mágico que concede a su portador el poder de dominar el mundo.

"El anillo de los Nibelungos" fue estrenado en forma completa en 1876

en Bayreuth (este de Alemania), donde se encuentra el teatro construido

especialmente para representar las obras de Wagner.

El proceso

de creación de la nueva producción de Lepage para la Met quedó retratado

en un documental llamado "El sueño de Wagner", estrenado el miércoles

en el marco del Festival de cine de Tribeca en Nueva York.

La

película, dirigida por Susan Froemke y que llevó cinco años de

filmación, "es una rara y fascinante mirada sobre el proceso artístico".

miércoles, 18 de abril de 2012

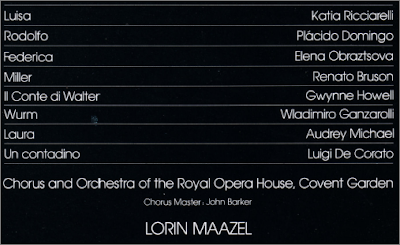

VERDI: Luisa Miller (Ricciarelli)

![Verdi: Luisa Miller - Ricciarelli, Domingo, Obraztsova, Bruson, Howell [Maazel] [2 CD]](http://www.tkshare.com/pic/20100529/2010052910531015.jpeg)

Luisa Miller puede considerarse la primera ópera "madura" de Verdi, antecesora inmediata de la gran trilogia romántica verdiana. Sobre un libreto en italiano de Salvatore Cammarano, basado en la pieza teatral Kabale und Liebe (Intriga y amor) de Friedrich von Schiller, Verdi construyó su 15.ª ópera, que marca el final de su primer período compositivo y el principio de su madurez. De esta ópera se suele grabar el aria de Rodolfo llamada Quando le sere al placido

Esta ópera se representa poco, a pesar de su indudable calidad; en las estadísticas de Operabase aparece la n.º 112 de las óperas representadas en 2005-2010, siendo la 41.ª en Italia y la catorce de Verdi, con 30 representaciones en el períodoDisfrútala en la maravillosa voz de la Ricciarelli!

Acto I

Escena 1: Un pueblo de El Tirol

El día del cumpleaños de Luisa, los campesinos se han reunido fuera de su casa para darle una serenata. Ella ama a Carlo, un joven al que ha conocido en el pueblo (Lo vidi e'l primo palpito /"Lo vi y mi corazón sintió el primer pálpito del amor") y lo busca entre la multitud. El padre de Luisa, Miller, está preocupado por este misterioso amor puesto que Carlos es un extraño. Carlo aparece y la pareja canta su amor (Dúo: t'amo d'amor ch'esprimere / "Te amo con un amor que las palabras apenas pueden expresar"). Mientras los pueblerinos se marchan para entrar en la iglesia cercana, a Miller se le acerca un cortesano, Wurm, que está enamorado de Luisa y desea casarse con ella. Pero Miller le dice que él nunca tomará la decisión en contra del deseo de su hija (Sacra la scelta è d'un consorte / "La elección de un marido es sagrada"). Irritado por su respuesta, Wurm le dice a Miller que en realidad Carlo es Rodolfo, el hijo del conde Walter. A solas, Miller expresa su enojo (Ah fu giusto il mio sospetto / "¡Ah! Mi sospecha era correcta").

Escena 2: Castillo del conde Walter

Wurm informa al conde del amor de Rodolfo por Luisa y ordena a Wurm llamar al hijo. El conde expresa su frustración con su hijo (Il mio sangue la vita darei / "Oh, todo me sonríe"). Cuando él entra, le dice a Rodolfo que se va a casar con la sobrina de Walter, Federica, la duquesa de Ostheim.

Cuando Rodolfo se queda a solas con Federica, él la confiesa que ama a otra mujer, confiando en que la duquesa lo entenderá. Pero Federica está demasiado enamorada de él para comprenderlo (D´´uo: Deh! la parola amara perdona al labbro mio / "Por favor perdona mis labios por las amargas palabras").

Escena 3: Casa de Miller

Miller le dice a su hija quién es Rodolfo en realidad. Llega Rodolfo y admite su engaño pero le jura que su amor es sincero. Arrodillándose frente a Miller declara que Luisa es su novia. El conde Water entra y se enfrenta a su hijo. Sacando su espada, Miller defiende a su hija y Walter ordena que tanto el padre como la hija sean arrestados. Rodolfo se alza contra su padre y lo amenaza:: si no libera a la muchacha, Rodolfo revelará cómo Walter consiguió ser conde. Aterrado, Walter ordena que liberen a Luisa.

Acto II

Escena 1: Una habitación en la casa de Miller

Los pueblerinos llegan donde Luisa y le dicen que han visto que a su padre lo arrastran encadenado. Luego llega Wurm y confirma que van a ejecutar a Miller. Pero le hace una oferta: la libertad de su padre a cambio de una carta en la que Luisa declare su amor por Wurm y afirme que ella ha engañado a Rodolfo. Al principio se resiste (Tu puniscimi, O Signore / "Castigame a mi, oh, Señor"), pero luego se rinde y escribe la carta al mismo tiempo que se la advierte de que debe mantener el engaño de haberla escrito voluntariamente y estar enamorada de Wurm. Maldiciéndolo (A brani, a brani, o perfido / "Oh, pérfido miserable"), Luisa sólo quiere morir.

Escena 2: Una habitación en el castillo del conde Walter

En el castillo Walter y Wurm recuerdan cómo el conde se alzó al poder matando a su propio primo y Wurm recuerda al conde cómo Rodolfo sabe esto también. Los dos hombres se dan cuenta de que, a menos que actúen juntos, pueden estar perdidos (Dúo: L'alto retaggio non ho bramato / "La noble herencia de mi primo"). Entran la duquesa Federica y Luisa. La muchacha confirma el contenido de la carta.

Escena 3: habitaciones de Rodolfo

Rodolfo lee la carta de Luisa y, ordenando a un sirviente que traiga a Wurm, se lamenta de los tiempos felices que pasó junto a Luisa (Quando le sere al placido / "Cuando en la tarde, en el brillo tranquilo de un cielo estrellado"). El joven ha desafiado a Wurm a duelo. Para evitar el enfrentamiento el cortesano dispara su pistola al aire, atrayendo al conde y sus sirvientes corriendo. El conde Walter aconseja a Rodolfo que vengue la ofensa que ha sufrido casándose con la duquesa Federica. Desesperado, Rodolfo se abadona al destino (L'ara o l'avella apprestami / "Prepara el altar o la tumba para mi").

Acto III

Una habitación en la casa de Miller

En la distancia, se oyen ecos de la celebración del matrimonio de Rodolfo y Federica. El viejo Miller, liberado de la prisión, regresa a casa. Entra en ella y abraza a su hija, luego lee la carta que ella ha preparado para Rodolfo. Luisa está decidida a suicidarse (La tomba e un letto sparso di fiori / "La tumba es un lecho con flores esparcidas"), pero Miller consigue persuadirla de que se quede con él. (Dúo: La filia, vedi, pentita / "La hija, veo, arrepentida"). Ahora a solas, Luisa sigue rezando. Rodolfo entra sin ser visto y vierte veneno en una jarra de agua sobre la mesa. Entonces le pregunta a Luisa si realmente escribió la carta en la que declara su amor por Wurm. "Sí," responde la muchacha. Rodolfo bebe un vaso de agua y luego pasa un vaso a Luisa y la invita a beber. Luego le dice que los dos están condenados a muerte. Antes de morir, Luisa tiene tiempo de decirle a Rodolfo la verdad sobre la carta (Duet: Ah piangi; it tuo dolore / "Ah, llora; tu dolor"). Miller regresa y reconforta a su hija moribunda; juntos los tres dicen sus oraciones y despedidas (Trío, Luisa: Padre, ricevi l'estremo addio / "Padre, recibe mi último adiós"; Rodolfo: Ah! tu perdona il fallo mio / "¡Ah! Perdona mi pecado"; Miller: O figlia, o vita del cor paterno / "Oh, hija, oh, vida del corazón paterno"). Mientras ella muere, los campesinos entran con el conde Walter y Wurm y antes de que él también muera, Rodolfo atraviesa con su espada el pecho de Wurm declarando a su padre La pena tua mira / "Observa tu castigo".

Verdi – Luisa Miller [Maazel]

EAC Rip | Classical (opera) | 2 CD | APE + CUE | NO Log | Covers | 284 mb (CD1) + 259 mb (CD2) | RS | TT 02:12:48

Released: 1980 | Label: Deutsche Grammophon | Recorded: 1980

Katia Ricciarelli, Placido Domingo, Elena Obraztsova, Renato Bruson, Gwinne Howell, Wladimiro Ganzarolli, Audrey Michael, Luigi de Corato

Royal Opera House Chorus and Orchestra, Covent Garden, Lorin Maazel (conductor)

If you\’re a Verdi enthusiast and own several Verdi operas (and I\’m quite sure La Traviata, Il Trovatore, Aida, Don Carlos and Otello are on that list) you will also want to collect this early Verdi masterpiece Luisa Miller. The bel canto influence is heavy here, and Verdi is already showing a flash of the musical power to cut through the beautiful music and reveal character psychology. Luisa Miller is a tale of a young woman\’s thwarted love amongst political intrigue during the late Renaissance. This 1980 studio recording stars Placido Domingo, Katia Ricciarelli, Renato Bruson and Elena Obraztsova. The conductor is Lorin Maazel leading the forces of London\’s Covent Garden. The strength of this recording is the genius of Maazel and the strong cast. Placido Domingo in 1980 was still in excellent shape, in fact entering the stage of his life in which he gained most notoriety. It was in the 80s when he appeared in the Franco Zefferelli opera films of Traviata (1982 with Teresa Stratas) and Otello (1986 with Katia Ricciarelli and Justino Diaz). His only true competitors then were Luciano Pavoratti and Jose Carreras. Domingo\’s talents were such that he was able to take on more roles than both Carreras and Pavarotti who sticked with the Italian repertoire. Domingo has sung in Spanish, Russian, German and French. Here is evident his gift for Verdi, which he still considers the composer who most helped his career.

Katia Ricciarelli as the titular heroine is extraordinary. Her voice is a mixture of beautiful high soaring lines and rich mezzo di voce and lower. Her dramatic strengths have never been more succinct than on this recording. Aria after aria, she proves she can master Verdi\’s smooth legato and bouncy coloraturas. But even more impressive is how well she sings with Placido Domingo in long-winded duets. Placido Domingo and Katia Ricciarelli worked well together, and in order for you to hear this for yourself just listen to their 1986 Otello and their studio recording on Deutsche Grammophone of the French version of Verdi\’s Don Carlos. Ricciarelli IS Luisa Miller, without any question as to how wonderfully she delivers. The only other soprano who is her equal was Anna Moffo, with a slightly more acrobatic voice than Ricciarelli and who recorde the role in the 60\’s opposite Carlo Bergonzi, Shirley Verrett, Reri Grist and is available on Amazon.com. Elena Obrazstova is a sensational, richly endowed mezzo soprano who makes the mezzo role sound even more electrifying than Ricciarellis limpid singing. Obraztsova also sounds great opposite Domingo and she sang a Carmen only about a year earlier in the Salzburg Festival in a Zefferelli production. Renato Bruson\’s baritone voice and style is incomparable and here he really proves how he could sound beautiful too. So there you have it. Go for this recording for the best modern Luisa Miller. — Amazon customer

password: aibdescalzo

Opera-Oratorio: BRUCH: Odysseus

Homer’s Odyssey in Music

By Leon BotsteinToday's revival of Odysseus by Max Bruch (1838-1920) brings back a work whose popularity was once extraordinary. The work was premiered in 1873. By the end of 1875 it had received over forty-two performances, an incredible statistic given the character of late nineteenth-century concert life. In 1893, when Max Bruch was awarded an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University, the celebratory concert opened with an excerpt from this work. It was the only one of Bruch's works represented at a concert chosen to honor the composer.

Perhaps the most important single vindication Bruch received concerning the value of this composition was the fact that Johannes Brahms chose to conduct the work himself in 1875 at the last concert of his career as music Director of the Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna. By the mid-1870s Bruch had already found himself compared more than periodically to Brahms as a close second . The decision by Brahms to devote the entire concert to this choral-orchestral work was high praise indeed.

As Bruch's modern biographer, Christopher Fifield, notes, the popularity of Odysseus lasted until the First World War. It did not survive the understandable and extensive anti-German campaign in England (where Bruch had worked and developed a significant following) during and after the war years. Furthermore, in Germany in the context of the Weimar Republic, the work was perhaps too reminiscent of the imperialist enthusiasms of the 1870s; too straightforward and sentimental; too detached from modernism. Not surprisingly, the archenemy of musical modernism during the 1920s, Hans Pfitzner, was one of Bruch’s leading posthumous advocates. In this sense, Bruch had the misfortune of living too long. In postwar Germany he became a visible and convenient contemporary symbol of an older generation's error-filled ways.

This issue of Dialogues & Extensions reprints the extensive description and analysis written by the eminent musicologist and critic Hermann Kretzschmar, whose 1887 guide book to the concert repertoire was among the first and most successful efforts in that genre. Kretzschmar's analysis, written more than a decade after the premiere of Bruch's Odysseus, is equivocal yet admiring. It is clear that Bruch and his best music had already suffered from a shift in expectations regarding what constituted "great" music. If it had been Bruch's intention to write large-scale choral and orchestral works using a musical vocabulary that could rival the Wagnerian achievement, he clearly failed. When Kretzschmar noted that Bruch's music in Odysseus, despite its evident quality, did not shift its character in relationship to the ancient Greek subject matter (i.e. from Bruch's earlier settings of Nordic materials), he was pointing to a perceived failure on the part of Bruch to connect non-musical and musical materials in a way that could bring about something new in music. The embrace of the tradition of classical antiquity as subject matter seemed to promise more.

Why was this shift in Germany during the 1870s to the world of ancient Greece significant? First, the success of Wagner had been so great that there were those who wished for a counterweight. Although Brahms had produced many great choral works, one large-scale work (the German Requiem), as well as a less successful cantata (Rinaldo), it was clear that the leading antipode of Wagner would remain active outside of the realm of dramatic music. He would continue to focus on instrumental forms, small choral works, symphonic music, and the song. Max Bruch, however, had made his career in the 1860s with some large-scale dramatic oratorios, as well as a large number of sacred choral pieces. Furthermore, he had written three operas, including one on the subject on which Felix Mendelssohn had worked at the end of his life, the Loreley. If one wanted to find an alternative to the Wagnerian within the framework of the traditions of musical classicism and early romanticism (e.g., Mendelssohn and Schumann), the hope lay in the work of Max Bruch.

The second reason is reflected in the fact that following the immediate success of Odysseus, Bruch went on to write an Achilles and a Leonidas. These efforts mirrored a romance with ancient Greece that flourished in the wake of Germany's unification and its successive defeats of Austria and France. In the early 1870s, in the eyes of its subjects, Imperial Germany seemed poised to take the place in modern history occupied by the Greece of antiquity. Antiquity was perhaps the only subject matter that could rival the nationalism evident in the Nordic and Germanic subject matter of Wagner's music dramas.

Part of the reason that Odysseus, Bruch's finest secular choral work, has fallen into oblivion despite its virtues is because the genre on which Bruch staked his claim against Wagner turned out to be a genre without a future. Bruch became the late nineteenth-century master of the secular oratorio–an unstaged dramatic form requiring large forces. Key to the success of these forces were amateur choruses, well-schooled singers who were members of the thousands of choral societies and clubs that dotted the landscape of English- and German-speaking Europe (and, for that matter, America, where this work was also popular). The nineteenth-century choral tradition was a participatory world of amateurs. Choral singing was among the most significant pastimes of the educated middle class. Its strength as a social and musical phenomenon was sufficiently great to influence the sort of music written by Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Brahms. Odysseus was the logical successor to Mendelssohn's St. Paul and Elijah and Schumann's Das Paradies und die Peri.

With the decline of musical amateurism at the beginning of the twentieth century, the popularity of large-scale secular choral music declined. Not only did the repertoire suffer, but by the early twentieth century the composers who wrote such music became tarnished by an association with a smug middle-class complacency identified with late nineteenth-century society. After the carnage of the First World War, both Mendelssohn and Bruch were seen as emblematic of sentimentality and artificiality. They were relics of a world of facades and pretensions to culture that masked an ugly and corrupt interior. The imperial Hellenism of the late nineteenth century became as suspect as the monumental historicism of late nineteenth-century architecture visible in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and London.

The modernist Austrian architect Josef Frank once remarked that it should come as no surprise that during the late nineteenth century, banks liked to have their buildings built in a neoclassical style. The Corinthian or Doric columns and the harmonious monumentality of nineteenth-century neoclassicism were designed to camouflage and dress up the ugliness and evil associated with modern capitalism. The dubious ethics associated with banking, including the wiping out of unwitting small investors or the calling in of mortgages of hard-working people caught in the web of fluctuating business cycles were sanitized by the symbolism of neoclassicism. Banking took on a nobility associated with the Delphic oracle and the rational philosophical wisdom of the ancients.

No doubt in the 1920s a young generation applied the same sort of critique to the libretto and music of Odysseus. But it is not at all clear what this kind of critique tells us today, more than a century after the work's premiere and several generations after the "new objectivity" of the 1920s. We forget that the 1870s under Wilhelm I should not be confused with the world of his totally reprehensible grandson Wilhelm II at the fin de siècle. Perhaps if Wilhelm I's son, the more liberal and decent Friedrich IIIl, had not been confined by incompetent medical care to a brief reign in 1888, European history might have taken a better turn. The culture of the late nineteenth-century middle class in Europe and England was not only about educated hypocrisy and superficiality. Bruch's Odysseus was in a form that made it an all-too-easy target of contempt and cynicism.

Max Bruch's music in Odysseus, "an agglomeration of beautiful musical ideas," as Kretzschmar put it, was designed to forge an immediate connection between performers and audience. The accessibility of the music and its structural clarity were intentional. The celebration of Homer was precisely that which Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer later pilloried in The Dialectic of Enlightenment. For Bruch's generation, Homer plausibly represented a tradition that contained a seemingly inexhaustible but relevant source of wisdom and greatness–an alternative to the mystical unreality of Wagnerian music drama. Hellenism of the late nineteenth century was an extension of the idealization of the Enlightenment, reason, and revival of classical antiquity associated with the mid-eighteenth century. At stake for Max Bruch and for his audience were notions of beauty, goodness, humanism, and heroism of a more admirable and comprehensible sort. There was nothing in Bruch that Max Nordau, the author of a famous book entitled Degeneration (published in 1892), would have called decadent and destructive.

No doubt the sentiments behind Bruch's use of the Homeric subject matter easily can deteriorate and slide into clichés. But if Bruch's achievement can fall prey to the accusation of over-simplification, Wagner's work can be accused of lending itself all too readily to murky and megalomaniacal illusions of profundity. In the final analysis, what this ASO performance should accomplish is the recreation of a work enthusiastically embraced by discerning performers and listeners for nearly half a century. It was one of the finest works written by a composer whose craft and talent were remarkable, earning him a secure place in music history.

After the famous G-Minor Violin Concerto, Odysseus was Bruch's most successful work. Wagnerian expectations need to be set aside. Free from the prejudices of early modernist criticism, we can encounter in this work a richness of musical invention, a powerful sense of drama, and a moving late-romantic evocation of the traditions of Handel and Mendelssohn. It is one of the many works in the overlooked genre of secular choral music of the late nineteenth century that demands a rehearing.